Vocabulary and the CEFR

The Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR) was developed to provide an outline around which language teaching could be standardized. So that classes, courses or materials described as being at a particular level would consistently cover more-or-less the same ground. The framework document itself is a series of can-do statements that describe the kinds of things that a learner should be able to do at each level, from A1 to C2, such as expressing number and quantity or describing daily routines. The CEFR doesn’t though list specific vocabulary.

CEFR labels in a dictionary

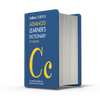

Since the CEFR was first published in 2001, a number of projects have sought to attach CEFR level labels to words to help teachers and syllabus designers align their vocabulary syllabus with the CEFR criteria. The new edition of the COBUILD Advanced Learner’s Dictionary, and its online version, shows CEFR labels at entries for key vocabulary. These have been allocated using a combination of the word frequency data that has always been a feature of COBUILD dictionaries and input from CEFR experts who checked how well vocabulary items matched the CEFR descriptors and assessed multi-sense words to allocate appropriate labels to each sense separately.

The labels cover A1 to B2 levels and include the basic core vocabulary that learners need to master to reach a B2 level of proficiency. Labels haven’t been included for the advanced C levels because the range of vocabulary relevant to learners at these levels, who might be studying academic English or Business English or English for specific purposes, is too varied.

But can we really say that words have levels? What are the benefits of labelling vocabulary in this way and what caveats do we need to bear in mind?

How can CEFR labels be helpful?

Consistency

As with the CEFR itself, one of the key benefits of having a guide to which vocabulary to focus on at which level is to ensure consistency. Teachers and syllabus designers can use the labels to guide decisions about vocabulary selection and progression to ensure that classes and courses at a particular level teach a broadly similar range of vocabulary and that as learners progress through the levels, they acquire that core repertoire of key words and phrases.

Focus and usefulness

As we will see below, vocabulary level labels aren’t intended to provide a restrictive list of those words that learners must study at each level. Instead, they indicate which words are likely to be most relevant and useful to learners at different stages of their learning.

Looking through old handouts I created at the start of my teaching career, there are plenty of examples of times I got carried away with a topic and threw a huge amount of rather randomly-selected vocabulary items at my poor students. Some of it was high-frequency vocabulary that they were likely to come across again, but much of it was quirky and maybe fun, but low frequency and probably not the best use of their time and energy. CEFR level labels would have helped guide my choices, not necessarily ruling out all of the quirky, fun stuff, but putting more emphasis on items that were likely to be more useful.

Similarly, after a lively class discussion, the board might be full of emergent vocabulary; words and phrases that have cropped up. However, not all of it will necessarily be equally useful for further focus. Checking the items against their dictionary CEFR labels can be a useful tool to help you, as a teacher, decide which of that language is worth further attention, recycling, and maybe inclusion in assessment.

But what about …?

It would be easy to see a vocabulary syllabus dictated entirely by CEFR level as a simple shortcut to what we need to teach. However, there are number of caveats to be kept in mind, the most important being that one size doesn’t fit all. This kind of framework will always be a generalization about what is broadly relevant to the average learner. We all know, though, that each class and each learner is different, and that recognizing these differences is essential to successful teaching and learning.

Context and needs

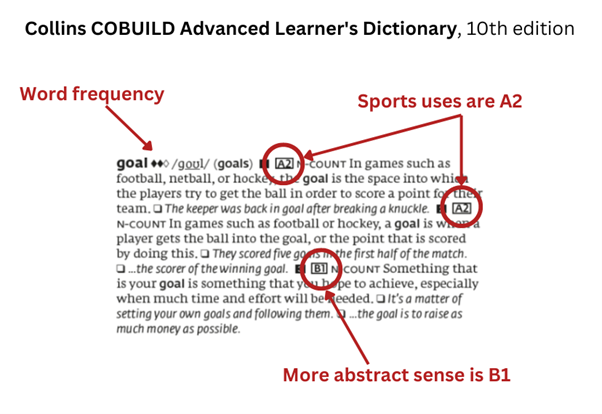

A basic framework of high-frequency vocabulary will only ever be just that, a framework. It will allow a learner to talk about generalities, but not necessarily the specifics of their own context. You can, for example, learn basic food-related vocabulary – meal (A1), vegetable (A1), dish (A2), spicy (B1+), portion (B2), etc. – but the actual foods and dishes you eat will depend on where in the world you live, your culture, and your individual tastes. Those specific food words might not have level labels in the dictionary, but if they’re part of your learners’ lives, then they’re relevant to teach. They’re what fills out that framework.

Collinsdictionary.com

CEFR level labels are also shown in the Collins COBUILD online dictionary.

Similarly, those learning English for the workplace will need to learn the vocabulary associated with their job. A hotel worker might need words like minibar, safe (as a noun) and buffet, all unlabelled. For these learners, these words won’t been seen as ‘advanced’ or ‘difficult’ because they express familiar concepts to them.

Relevance vs. difficulty

Vocabulary CEFR labels are often misperceived as indicating how ‘difficult’ a word is, with unlabelled words classed as ‘hard’. This is far from the case. Arguably, any concrete noun that can be illustrated in a picture is as easy for a learner to understand as any other.

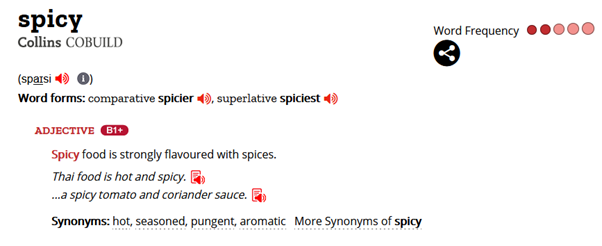

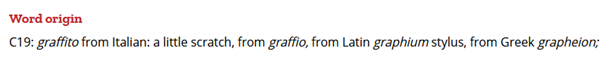

As a materials writer, for example, I might want to compile a B1 reading text about the topic of graffiti, only to find that graffiti is unlabelled and so ‘above level’. I can see that it’s not a high-frequency, core word and I may not want to add it to my vocab syllabus, but with a simple image to accompany the text, it’s not going to be ‘too hard’ for the learners and will make for a more engaging text.

The influence of L1

What’s more, graffiti is a word from Italian, so it’ll be immediately familiar to Italian speakers, not to mention speakers of French, German and Spanish, for whom it’s also a loan word. English is a historical mishmash of borrowings from different languages meaning that for speakers of many languages, there will be numerous cognates.

Labels as part of your toolbox

All of these caveats about how we can use - or ignore - level labels don’t, I believe, diminish their usefulness. The labels still provide a principled, researched-based criteria for guiding, rather than dictating, vocabulary selection. They need to be used in an informed way as part of your teacher’s toolbox alongside the other criteria mentioned above to help you choose the vocabulary that will be most relevant and useful to your learners; what to focus on, what to recycle and revisit, what to leave out, and what to include for interest, but emphasize less.

This blog post has been written by Julie Moore. Julie is a freelance ELT writer, lexicographer, corpus researcher and teacher trainer. Over 20 years, she’s written for a wide range of published ELT materials including learner’s dictionaries, self-study materials and course books.

Find out more about our new editions of the Collins COBUILD dictionaries and other COBUILD materials here.